[This is the seventh of an ongoing series that examines the rise of writing – and therefore reading – around the world. We will be looking at the major developments and forces that shaped the written languages we use today. Links to all the previous posts are listed at the end of this one. This was originally published on the AceReader, Inc. blog.]

The Japanese writing system, which migrated from China to Japan during the 5th century CE, is notable for its interesting history. It is a complex logosyllabic system, featuring a combination of Chinese logograms, two Chinese-derived syllabaries, and Japanese innovations to meet the language’s own unique needs. The first Japanese texts were written in Chinese characters (kanji), using a system called kanbun (which simply means “Chinese writing”). This was not tremendously successful, as Japanese grammatical syntax differs considerably from that of the Chinese. The Japanese solved this problem by keeping the Chinese characters but using their own grammar instead. [1]

Another problem that occurred in the transition was that, as we saw in the last post, Chinese is an isolating language (i.e., nouns and verbs don’t change structure – the words around them indicate the needed change of structure and meaning); this led to a writing system where each individual sign represented a morpheme. The Japanese language, on the other hand, has inflected verbs and postpositions; these require the addition of suffixes and particles to words and clauses.

To represent these extra grammatical units, Japanese scribes used specific Chinese characters that indicated sound values. This system was ambiguous – it was difficult to tell whether a character should be interpreted as a logogram or as a phonetic sign, and the difficulty led to a change in how the syllabograms were graphically indicated. The Japanese took the Chinese characters used to indicate sounds and visually simplified them, making them distinct from the Chinese characters used as logograms.

The Japanese syllabic grapheme is referred to as a kana. There are two sets of kanas: hiragana, and katakana.

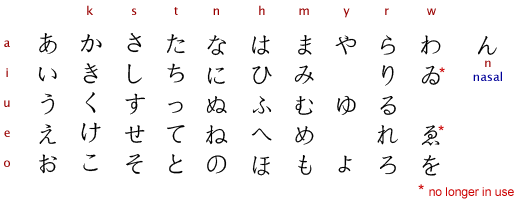

Hiragana came into use in the 8th century CE, where the Chinese characters were used only for their phonetic values. This system was known as the manyogana, taken from the name of the anthological work “Manyoshu.” Eventually, the original signs were reduced in number and simplified into sogana, finally arriving at the hiragana form. At first, literate men scorned the hiragana since Chinese was considered the “cultured” language. Women, on the other hand, were not allowed to learn the Chinese characters, and so they relied on the hiragana. “The Tale of Genji,” the world’s first novel, was written by Lady Murasaki Shikibu in hiragana. Over time, the gender-based segregation of literacy dissolved, and hiragana became an accepted literary script. Today, hiragana is used to write native Japanese words.

The following is the hiragana syllabary:

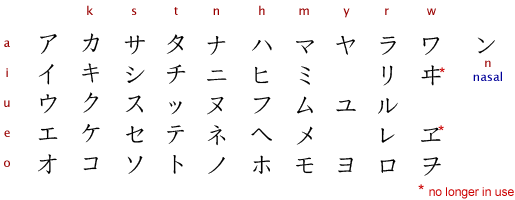

The second Japanese syllabary is called katakana, and it was originally used as a pronunciation aid for Chinese Buddhist scriptures. However, over time, it became a way to write grammatical suffixes and particles, while kanji remained the root of the word. Today, katakana is often used to write non-Chinese loan words.

Katakana syllabary

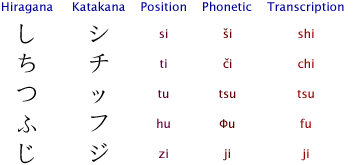

Some special syllabograms in both hiragana and katakana reflect Japanese allophones, which are different physical sounds perceived as the same sound by native speakers. Typically the position of a kana in the grid (such as the one above) determines its pronunciation, but these special signs are pronounced differently. For instance, the hiragana sign し is located in the s column and i row, which means it should have the phonetic value of /si/. But instead it is pronounced as /ši/ (like the English she). As a result, /s/ and /š/ before the vowel /i/ are allophones and are perceived as the same consonant.

Japanese allophones

In addition to the kanas, modern Japanese writing contains about a thousand Chinese characters, or kanji, used to write words that are either native Japanese or Chinese loans. Often times, Japanese names (personal, geographical, etc.) are written completely in kanji, and some words (both Japanese and Chinese loans) would be written as kanji as well.

If you look a Japanese newspaper, you’ll probably see representations of all three of these writing systems.

Next up: The Olmecs of Mesoamerica

Citation:

[1] Lo, Lawrence. (2012). “Japanese.” AncientScripts.com. Retrieved from http://www.ancientscripts.com/japanese.html

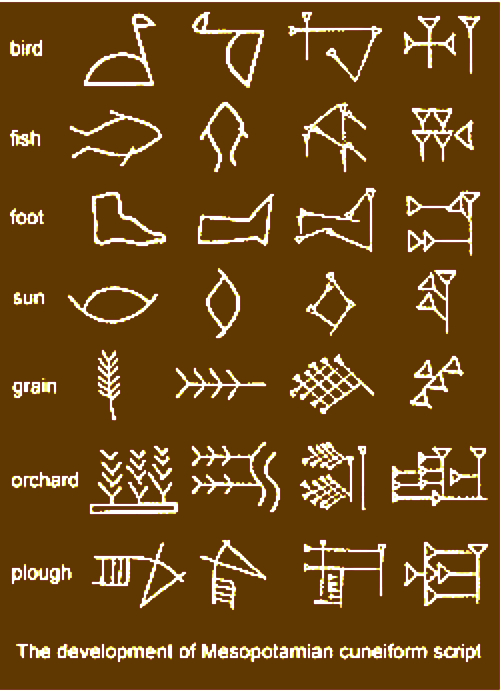

To read Part 1 (Sumerians), click here.

To read Part 2 (Egyptian hieroglyphs), click here.

To read Part 3A (Indo-European languages part 1), click here.

To read Part 3B (Indo-European languages part 2), click here.

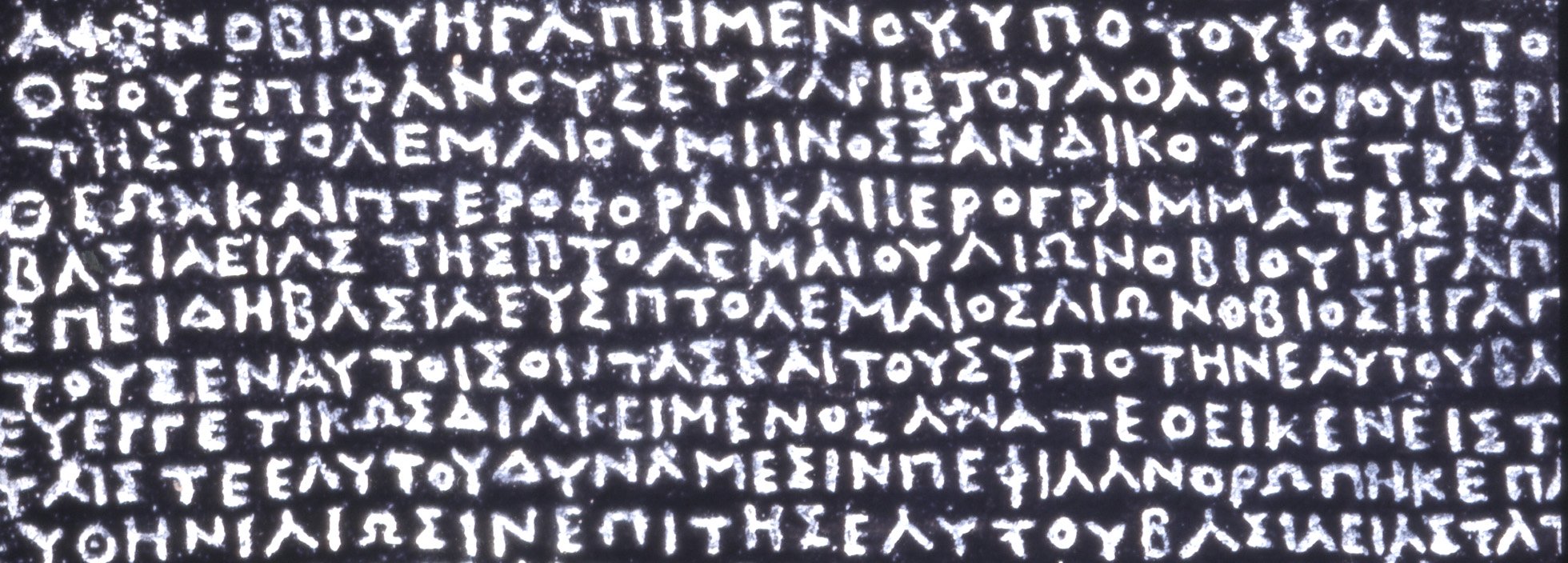

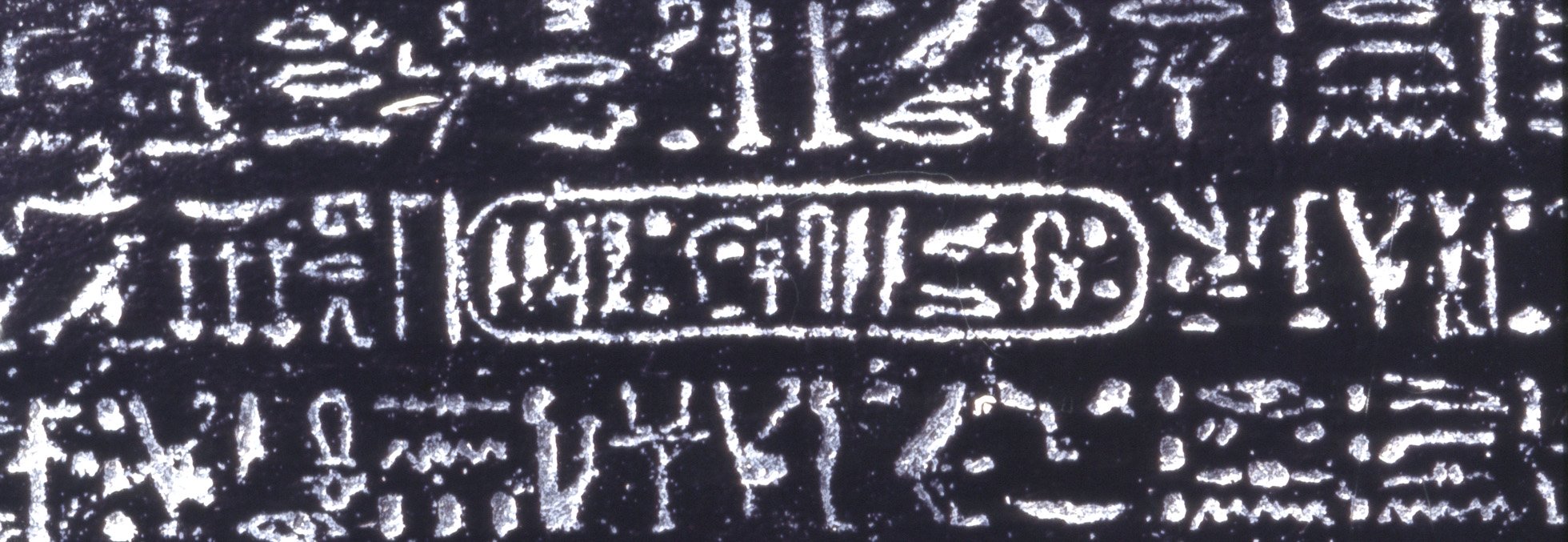

To read Part 4 (Rosetta Stone), click here.

To read Part 5 (Chinese writing), click here.